March 22, 2022

Where Have All the Big Cypress Gone?

If you’ve driven along US 41 or I-75 through Big Cypress National Preserve, there’s no doubt that you’ve marveled at beauty of the cypress trees that are patchworked into the sawgrass prairies throughout this swampland. Maybe you’ve even ventured out into wilderness to experience these trees up close and personal for yourself.

With long, vibrant green needle leaves in the summer and starkly bald branches in the winter, these cypress trees give those of us that live in southern Florida’s land of eternal summer a visual snippet of the changing seasons that our contemporaries up north experience.

But if you think the cypress trees that you see today are lush and plentiful, would you believe that they used to be even more so?

In the decades surrounding the founding of the United States, most harvesting activities along the East Coast concentrated on hardwood and pine forests, but historical documentation suggests that logging of bald cypress swamps was occurring as early as the eighteenth century.

By the early 1900s, when old growth cypress swamps in other parts of the country were depleted, the industry’s attention turned to the southern extent of the species in Florida, a region that had been considered inaccessible until that point.

After extraction of mature trees in Fakahatchee and Corkscrew, logging crews turned their attention to the remaining old growth cypress strands (long, narrow swamps characterized by a deep peat substrate) of what is now Big Cypress National Preserve.

The heartwood of old growth cypress timber was valuable for its workability, resistance to rot and water damage, as well as its rich reddish color. During the peak of the old growth cypress logging period in Florida, 300 million board feet were harvested annually. Harvesting of cypress timber within Big Cypress National Preserve lasted until the late 1950s.

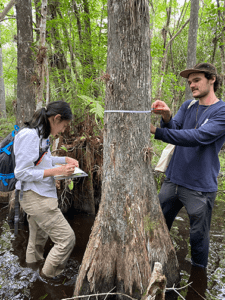

The Alliance recently funded a study within Big Cypress, led by a team from Florida International University, to see just how these logged areas have recovered and how these areas could be better managed in the future. This is the first time in over 70 years that the effects of cypress tree foresting has been studied in this area.

Over the course of five months, the team studied 19 plots throughout the Gator Hook and Roberts Lake areas of Big Cypress, collecting data on a range of metrics, including the size of current cypress trees, the size of the stumps of previously harvested trees, and the range of plant life that are found within.

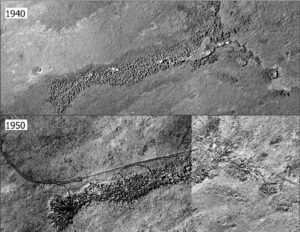

Using a combination of historical aerial photograph interpretation and remote sensing, the team also visually reconstructed forest continuity in this part of Big Cypress.

So just what was discovered?

- A total of 110 plant species and 56 families were found across the 19 plots.

- The stumps of previously logged cypress trees ranged up to 150 cm or close to 5 feet in diameter.

- The greatest diameter of a current living cypress tree recorded within these plots was 107.5 cm or about 3.5 feet.

- These large living trees provide a look into a different era of Big Cypress’ history. They can potentially provide information on past climate trends, as well as important genetic information that might lend to our understanding of long-term forest adaptive capacity.

- Results of the mapping exercise determined a significant change in tree stems and canopy cover from the 1940 aerial photos (pre-logging intervention) and the 1953 photo, with much of the full canopy cover still missing in 2020.

- Twenty-one species of special concern were identified, including the 10 orchid and bromeliad species on the “State Endangered” list. Only four non-native plant species were found in the plots and of these, only one is considered invasive (Brazilian pepper).

Has this logging left a lasting impact?

Despite the expansive removal of large cypress stems, the forest in these strands did recover.

The question remains, however, if cypress trees will ever return as the dominant species in this system. While invasive species were rare to non-existent in the site, the original cypress strand could eventually be replaced by the native hardwood and mixed swamp forest types, which has been documented by researchers in other logged cypress sites throughout Florida.

The high potential for restoration through nature just running its course lends credence to the idea that these secondary forests can still serve as an important biodiversity reservoirs.

And because of this study, there is now a baseline for future monitoring to continue, which is increasingly important with all of hydrological endeavors being implemented throughout the greater Everglades ecosystem.

Understanding the history of our land is important to guiding its future. Projects like this are only possible with your support. Donate today.